Edward Steichen was a giant in the field of photography and so it almost goes without saying that anytime his photographs are present in an old magazine they are collectible. But good luck to the low-budget collector attempting to acquire original Steichen pieces on the cheap — the Edward Steichen page on Wikipedia notes that a print of an early Steichen photo, The Pond Moonlight (1904) sold at auction in early 2006 for $2.9 million. Okay, that’s a bit extreme, but later Steichen photos cost a few bucks as well. You could always collect reproduction prints, but if you’re like me you want to spend a few dollars and be able to own something a little older and more collectible than a copy. Once again, collecting old magazines featuring Edward Steichen’s work is the way to go!

Most rare are early issues of Camera Work, published by Steichen’s friend and fellow legend in the field of photography, Alfred Stieglitz. First of all, good luck finding these, and finding them intact, secondly these aren’t exactly a low budget collectible themselves. But there is an alternative.

First, a little quick background information: Edward Steichen, born 1879 in Luxembourg, came to the United States in 1881 and became a naturalized citizen in 1900. Though Steichen took up photography in 1895, he considered himself primarily a painter up until about 1920, when he confirmed his faith in photography by burning all of his paintings. Steichen had been a Pictorialist up until this time, believing photography should emulate painting, but after commanding the photographic division of the American Expeditionary Forces in World War I and by the time he returned home to conduct his famous bonfire his artistic forces had come to stand for something else:

“Today I am no longer concerned with photography as an art form. I believe it is potentially the best medium for explaining man to himself and to his fellow man.

Later in his life this would be the basis for his “The Family of Man” exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Steichen was the head of MoMA’s Photography Department at the time of the 1955 exhibition, which contained over 500 photographs taken by 273 photographers, from the famous to the anonymous, located in 68 different countries. There’s an excellent article over at the International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum which focuses on “The Family of Man” exhibition.

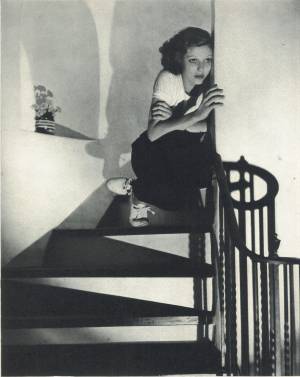

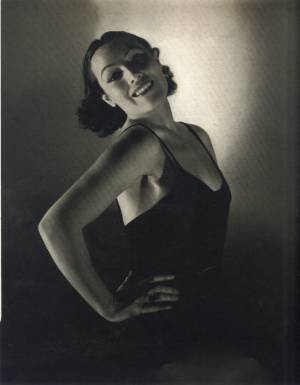

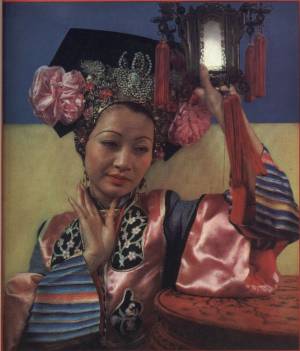

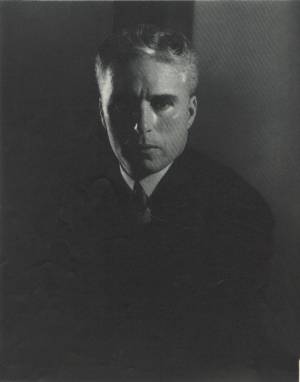

But the work which we are primarily concerned with here was done in the period in between, when from 1923 through 1937 Edward Steichen was employed as the chief photographer for Conde Nast Publications, publishers of both Vogue and Vanity Fair. All of the photographs shown on this page were taken by Steichen for Vanity Fair and appeared in a few issues that I had acquired near the time of writing which are either for sale or have recently sold.

Most interesting in relation to Edward Steichen, is the June 1932 issue of Vanity Fair which includes an article about Steichen written by Clare Booth Brokaw (yes, she would later marry Time, Inc’s own Henry R. Luce and be better known to us today as Clare Booth Luce). Though especially associated with Vanity Fair for his Hollywood celebrity portraits, as the majority of images on this very page attest, Brokaw lists several of the personalities who had posed for Steichen over the years:

“To mention only names which are today in the public eye (Steichen’s files would be a veritable tomb of now forgotten idols) Winston Churchill, Jascha Heifetz, Eugene Meyer, Paul Cravath, Ruth Draper, Jack Dempsey, Gene Tunney, Lily Pons, Lucrezia Bori, all the Barrymores, H.G. Wells, Walter Damrosch, H.L. Mencken, Baron von Kuhlman, George Jean Nathan, Walter Lippmann, Eugene O’Neill, Paul Morand, Henri Matisse, Samuel Seabury, Gerhart Hauptmann, Thomas Lamont, and for Vogue, most of the Vanderbilts, Whitneys, Morgans, Rockefellers, Harrimans, not to mention lesser social and artistic fry.”

Steichen earned money from commercial photography as well, Brokaw continues:

“…he takes pictures of sunburned arms for Jergens’ Lotion, of bedrooms for Simmons’ beds, of fashions for Vogue, of the aristocratic users of Pond’s extract, of match boxes, sugar cubes, coffee seeds for Stehli silk designs. These fine examples of commercial art reach, in the magazines and papers of one sort or another, the entire literate population of the United States. It is, in fact, in the commercial field that Steichen has exercised the greatest influence.”

Brokaw continues to discuss the talents of Steichen in remarking how he excelled in photographing insects and flowers. She writes “…with the same vigorous sympathy he can photograph the George Washington Bridge, or a lotus flower.” The article covers all or parts of 3 pages and pretty much covers Edward Steichen’s entire career through 1932, at which time he was already considered a master in the field of photography.

When Vanity Fair folded in 1937 Steichen retired from commercial and fashion photography, and he went on to take photos for the Roosevelt administration programs, worked for the military again during World War II as director of the U.S. Naval Photography Division, and took over the MoMA post and put together “The Family of Man” exhibition, which would tour 37 countries over the next eight years. Edward Steichen died in 1973.

The images that appear above and below are all from issues of Vanity Fair.

Sources:

- Brokaw, Clare Booth. “Edward Steichen, photographer.” Vanity Fair. June 1932: 49.

- “Edward Steichen.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 29 Jul 2006, 12:49 UTC. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 1 Aug 2006 < http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Edward_Steichen&oldid=66517076 >.

- “Edward Steichen (1879-1973) The Family of Man.” International Photography Hall of Fame, Inductees. 2004. 1 Aug 2006. < http://www.iphf.org/inductees/esteichen.html >

- Livingston, Dr. Valerie. “Edward Steichen and the Advent of Hollywood Celebrity Portraiture in Vanity Fair: 1923-1937.” Susquehanna University, Lore Degenstein Gallery. 7 Sep 2004. Susquehanna University. 1 Aug 2006. < http://www.susqu.edu/Art_Gallery/steichen/ >