I’d originally mentioned this article as especially capturing my attention this past Thursday, when we paged through this entire issue of Harper’s Monthly. Titled “A Wonderful Escape from an Austrian State Prison” it’s about 19th century Italian Revolutionary Felice Orsini.

I’m so glad this one caught my eye, as I’m not ashamed to admit that though Orsini’s name may have rung a distant bell to me, I had no idea why. Not only did I learn about him through the article, upon finishing I needed to know how Orsini’s life turned out. The answer to that question would be short, as he was executed within a year of the cover date.

This Harper’s Monthly article gives some backstory on Orsini, but really excels with the details of his escape. How embellished these details are I don’t know, but they made for great reading so I figured I’d share. I’m going to quote the original text quite a bit here, then wind up with a brief summary of that final year of Orsini’s life, that portion mostly cribbed from Wikipedia.

Here is Orsini’s backstory in the words of the author:

Born of parents in easy circumstances, well educated and bred to the law, endowed with rare qualities, decision, clear mind, courage, patience, his life is a crushing reproach to the rulers of Italy. He has never been any thing but a revolutionist. At twenty-two he conspired against the Pope. At twenty-five he was a state prisoner, in a cell six feet by four, on a general charge of being a dangerous man; and shortly afterward, having undergone an examination of fifteen minutes, was condemned to the galleys for life. At twenty-seven he, with two thousand others, was set at liberty by Pope Pius the Ninth, who desired to inaugurate his accession by a gracious act of clemency. At twenty-eight he was conspiring again in Tuscany, and again in the hands of the police. At twenty-nine he was a leader of the Roman revolutionists. At thirty-three he was conspiring in Piedmont, was caught, imprisoned, kept in durance vile for a couple of months, then shipped off to England…In 1854 he was in Italy again, conspiring for a general uprising, and dodging the gens-d’armes; and in the fall of that year, having gone to Transylvania to see about a conspiracy there, he was caught again.

The court held a note written in Orsini’s hand containing instructions to his fellow revolutionaries. Knowing the eventual outcome Orsini, after admitting he had written the note, said to the court, “Instead of dying for my country on the battle-field, I shall die for her on the scaffold. Sooner or later it must have ended thus.”

The prison conditions were described as follows:

The condemned shall be confined in a dungeon secluded from all communication, with only so much light and space as is necessary to sustain life. He shall be constantly loaded with heavy fetters on the hands and feet. He shall never, except during the hours of labor, be without a chain attached to a circle of iron round his body. His diet shall be bread and water; a hot ration (slices of bread steeped in hot water and flavored with tallow) every second day; but never any animal food. He bed shall be composed of naked planks, and he shall be forbidden to see any one without exception.

Orsini resigned himself to this lifestyle, accepting that death would soon end it. He was ready to become a martyr. But then communication with the prisoner in the next cell led him to discover that the man was his favorite fellow-conspirator, Calvi. Once Calvi was put to death, Orsini decided that he must survive. A volume of Byron loaned to him by a jailer awoke in Orsini not only the will to live, but the desire to escape.

I included the author’s account of the cell, but now here is how it now looked through the eyes of Orsini:

The cell in which he was confined had but one window, seven feet from the floor, in the embrasure. Twelve iron bars, three inches thick, crossed each other, and were inserted in the stone casement; and a second frame-work of similar bars occurred at three feet distance. The outside of the window was covered with an iron grating. From the window to the ground outside was one hundred and four feet, and this ground was the bottom of a wet ditch. On the other side of the ditch ran a wall perpendicular for twenty feet, and very thick. And this wall surmounted, there yet remained a bridge to cross, which was closed at night, and guarded by armed sentinels.

Orsini befriended his jailers and somehow came into possession of a small bundle of steel saws. He decided to work under the distractions of the day time feeling that the noise he created at night would be too much and could not be masked. When Orsini finally sawed through the first layer of bars he couldn’t resist crawling up to see if he fit–he did, but once crammed into the little space he could not get out! Luckily the jailer was late on rounds that night and Orsini finally managed to twist himself back into his cell.

The second layer of bars was thicker, so he decided to only saw through one of them and then work at the adjacent stone-work to widen his space for escape. He gathered sheets and towels which he tore into strips in order to make a rope to descend upon. Overwhelmed with excitement, Orsini aborted his first attempt, but he remained calm enough the next night to even pen a letter to the governor before lying down to await the jailers’ final pass for the evening.

Here is his escape:

The turnkeys came, as usual, and went away without remark. As they entered the next cell, Orsini climbed the window, and groped through his hole. Clutching the rope with his hands, he wound his legs round it, and began his descent. After he has descended about eighty feet, he felt his arms, which were unused to such labor, giving way; he saw a ledge in the wall, and tried to gain it to rest himself; but in doing so the cord slipped from his legs, and he hung by his arms alone, and began to swing. ‘Twas but for a moment. He would probably have fallen at any rate; but, looking down, he fancied he saw the ground six or seven beneath him, and let go.

He had no idea that the whole life of man was so long as the period he took to fall.

He fell twenty feet or more, striking first his knees, then his feet against a mass of cement, mud, and brick. Of course, he lost consciousness. When he came to himself he fancied that his right leg and arm were both broken.

In such immense pain he no longer cared what happened to him, Orsini, after an attempt to rise from the ditch he’d landed in, decided to give in to his body and fell asleep. He woke an hour later due to the pain and had his spirit refreshed with his nap. He called out to pedestrians to help him from the ditch, with no luck at first, but finally enlisting the aid of a couple of passers-by.

Once freed Orsini told them, “Understand what you have done. I am a political prisoner.” The men ran from him, and Orsini, wanting to escape the general location of the prison, followed.

And so the article ends, well, actually not quite. The author suspects Orsini will find trouble again, as his history dictates that is inevitable.

The author was correct.

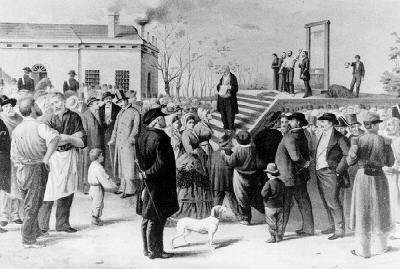

Orsini developed a political grudge against Napoleon III and on January 14, 1858 Orsini and accomplices would throw three bombs at the imperial carriage which carried the Emperor and Empress. 8 people were killed, another 142 wounded, and Napoleon III and his wife weren’t among either group. Justice was swift as Orsini was guillotined March 13 the same year, a day shy of two months after the incident.

Just another story inside one of my old magazines. Is it any wonder I get so much enjoyment out of them? This issue was damaged, without any potential value, so I actually got to have a pretty good time with it, marking it up as I read, dog-earing pages, even fell asleep with it gripped in my hands one night. Certainly not the way I’d treat an issue intended for sale. Anyway, I mention this because I have a pretty nice sized stack of damaged Harper’s from the 19th Century and I think the tale of Orsini has inspired me to eventually make my way through them all in this space.