Our Random Issue this month is the June 1932 issue of Vanity Fair. While putting this issue together I also created a page giving a brief history of the 1914-36 version of Vanity Fair as it was under Frank Crowninshield.

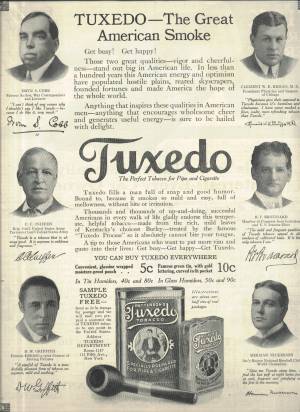

The June 1932 issue of Vanity Fair comes with a 35 cent cover price, or you could subscribe for $3.00 for the entire year. The issue is 72 pages plus covers. Advertising is split between the front and back of the issue, with all of the editorial content coming in between. At the beginning of the issue are 11 full-page ads plus various guides which include both text and display advertising. “The Dog Directory” page includes a short article, “The Pug Comes Back”, which is just under a half a page with ads surrounding it. The “Vanity Fair Travel Directory” contains a page of what looks like classified ads followed by another 3 pages of larger ads. Finally, “The Shoppers’ and Buyers’ Guide” is a single page including both text and display ads.

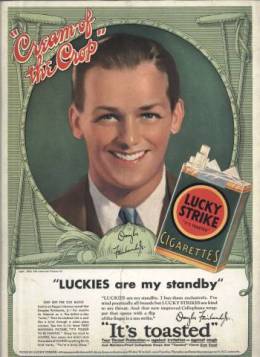

At the back of the issue, after most of the content but interspersed with the continuations of several stories are another 10 pages of full-page ads, plus a total of 5-3/8 pages of ads totaling a half page or less. The covers have a colorful Ethyl Gasoline ad illustrated by Karl Godwin on the inside front cover, a Goodyear ad on the inside back cover, and a Lucky Strike Cigarettes ad on the back cover featuring a large image of Douglas Fairbanks Jr. If you include the covers as pages, which you really must since that space costs more than inside pages, the June 1932 issue of Vanity Fair contains a total of approximately 35-1/4 pages of advertising over 76 pages total, leaving us with 40-3/4 pages of text, photos and illustrations with which we can travel back in time.

At the back of the issue, after most of the content but interspersed with the continuations of several stories are another 10 pages of full-page ads, plus a total of 5-3/8 pages of ads totaling a half page or less. The covers have a colorful Ethyl Gasoline ad illustrated by Karl Godwin on the inside front cover, a Goodyear ad on the inside back cover, and a Lucky Strike Cigarettes ad on the back cover featuring a large image of Douglas Fairbanks Jr. If you include the covers as pages, which you really must since that space costs more than inside pages, the June 1932 issue of Vanity Fair contains a total of approximately 35-1/4 pages of advertising over 76 pages total, leaving us with 40-3/4 pages of text, photos and illustrations with which we can travel back in time.

Unlike other periodicals of this time, Vanity Fair made use of the photograph as an art form rather than as just another tool of reportage. Several photographs in this issue are by Edward Steichen, who was the chief photographer for Conde Nast publications from 1923 through 1937. At the bottom of that Steichen page are several examples of his photographs from various issues of Vanity Fair that I have had for sale. The first such photo is from this June 1932 issue, and is of movie actress Lupe Velez. While most associated with Vanity Fair for his photographs of movie stars such as Mexican Spitfire Velez, Steichen’s Vanity Fair photos were more accurately a Who’s Who of the public and pop culture of his time. Yes, there’s a Steichen photo of starlet Dorothy Jordan in this issue, as well as German import to Hollywood Dita Parlo, but also found in this issue are photographs of senior partner of J.P. Morgan & Company Thomas W. Lamont and from the world of sport, Pacific Coast swimming champion Olive Hatch.

Unlike other periodicals of this time, Vanity Fair made use of the photograph as an art form rather than as just another tool of reportage. Several photographs in this issue are by Edward Steichen, who was the chief photographer for Conde Nast publications from 1923 through 1937. At the bottom of that Steichen page are several examples of his photographs from various issues of Vanity Fair that I have had for sale. The first such photo is from this June 1932 issue, and is of movie actress Lupe Velez. While most associated with Vanity Fair for his photographs of movie stars such as Mexican Spitfire Velez, Steichen’s Vanity Fair photos were more accurately a Who’s Who of the public and pop culture of his time. Yes, there’s a Steichen photo of starlet Dorothy Jordan in this issue, as well as German import to Hollywood Dita Parlo, but also found in this issue are photographs of senior partner of J.P. Morgan & Company Thomas W. Lamont and from the world of sport, Pacific Coast swimming champion Olive Hatch.

Another interesting feature in this issue is an article about the man himself, “Edward Steichen” by Clare Booth Brokaw, who would yes, soon through marriage come to be know as Clare Booth Luce. The Steichen article was excellent and informative, so much so that I won’t detail it here because I relied on it to great degree for the Steichen page of CollectingOldMagazines.com that is referenced above.

Other portraits in this issue are by Baron George Hoyningen-Huene, originally of St. Petersburg Russia, and by this time chief photographer for the French Vogue. Hoyningen-Huene’s photos in this issue are of actress Ina Claire, winking while holding a drink as the caption explains she is “celebrating her proposed return to the Manhattan stage this autumn, after serving out a three-year sentence in Hollywood.” More notable by Hoyningen-Huene this issue is the page titled “Tarzan of the pools” which contains a large full-length photo of Johnny Weissmuller of whom the caption says he had “retired two years ago from active sports to take a job as salesman for the B.V.D. Bathing Suit Company.” While noting the possibility of a sequel, it’s no surprise to hear Vanity Fair speak somewhat mockingly of Weissmuller’s most recent endeavor, the “gorgeous piece of hokum” which was Tarzan the Ape Man.

Other portraits in this issue are by Baron George Hoyningen-Huene, originally of St. Petersburg Russia, and by this time chief photographer for the French Vogue. Hoyningen-Huene’s photos in this issue are of actress Ina Claire, winking while holding a drink as the caption explains she is “celebrating her proposed return to the Manhattan stage this autumn, after serving out a three-year sentence in Hollywood.” More notable by Hoyningen-Huene this issue is the page titled “Tarzan of the pools” which contains a large full-length photo of Johnny Weissmuller of whom the caption says he had “retired two years ago from active sports to take a job as salesman for the B.V.D. Bathing Suit Company.” While noting the possibility of a sequel, it’s no surprise to hear Vanity Fair speak somewhat mockingly of Weissmuller’s most recent endeavor, the “gorgeous piece of hokum” which was Tarzan the Ape Man.

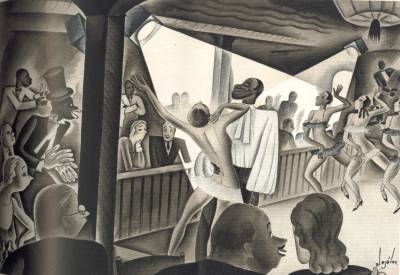

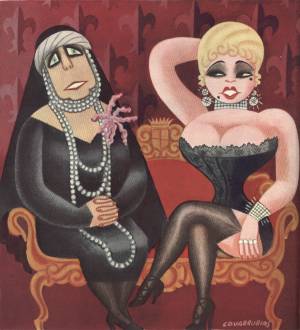

Beyond the sharp shadows and deco settings of the black and white photography featured throughout Vanity Fair, every so often color blazes across the page as you stop to stare at a detailed full-page caricature. The opening article of this issue, “The Taxpayer’s Orgy”, is the right hand page facing William Cotton’s caricature of Secretary of the Treasury, Ogden L. Mills. But even more interesting nestled into the middle of the issue is #7 of the “Impossible Interviews” series by Miguel Covarrubias. I’ve created a page on the site similar to the Steichen page for Covarrubias, which includes several samples of his work including this issue’s “Marie of Roumania versus Mae West” feature.

The captions for “Impossible Interviews” were written by Vanity Fair contributor Corey Ford. In this issue the Romanian Queen laments her neglect by the public, to which West replies “What I mean, Sister, lemme put you wise. Royalty don’t get you any place, any more. Today they only want the kind of a Queen they can hold on their laps. Lookit, me, for instance. Every other inch a Queen, from hips to whoozis.” The conversation is only a few inches of text, though Covarrubias’ art tells the whole story.

The captions for “Impossible Interviews” were written by Vanity Fair contributor Corey Ford. In this issue the Romanian Queen laments her neglect by the public, to which West replies “What I mean, Sister, lemme put you wise. Royalty don’t get you any place, any more. Today they only want the kind of a Queen they can hold on their laps. Lookit, me, for instance. Every other inch a Queen, from hips to whoozis.” The conversation is only a few inches of text, though Covarrubias’ art tells the whole story.

There are smaller images, both photographic and illustrated, throughout the issue accompanying the articles, and we’ll take a look at those as we cover them. Which we are now about to do. As mentioned, there is the article about Steichen in this issue authored by Clare Booth Brokaw (Luce) and the lead article was already mentioned as well, “The Taxpayers’ Orgy” was written by Marcus Duffield and is about the expense of democracy, especially as the U.S. pulls itself out of Depression. Also included on the pages of the Duffield article are photographs of Paul Manship’s monument of Abraham Lincoln “The Hoosier Youth,” which is to be officially unveiled in Fort Wayne on July 4th. It will stand in the forecourt of the Lincoln National Life Insurance Company’s new building.

But even mentioning those two articles is skipping a little ahead of ourselves. Beyond the advertising found up front, but before the contents page, is “The Editor’s Uneasy Chair”, which I assume was actually penned by Frank Crowninshield. The construction of this editor’s page is interesting, as it alternates Crowninshield’s text about items found inside this issue, such as a little bit about Edward Hopper, who has two of his paintings reproduced in full-color inside, followed by a letter from a Vanity Fair reader. The editor does not reply to the reader’s letters, he just allows them to stand on their own whether they be flattering to Vanity Fair or antagonistic enough as in the case of one found here that is signed “Yours disgustedly.”

Turning the pages we then see the contents page, the Duffield article and Hoosier Youth photos, and then Steichen’s portrait of Lamont. Following this is Jefferson Chase’s article “The national straw-vote season” which is mostly about straw-votes in general, but more interestingly comments specifically on The Literary Digest and it’s popular straw polls which had correctly choose Coolidge in 1924 and Hoover in 1928. The Digest would be correct again for this election, but would bring disgrace upon itself in 1936 when it notoriously chose Alf Landon to defeat F.D.R. in a landslide.

Chase’s article, satire dripping with sarcasm, then suggests that the American public, sick of having its time wasted, should prefer to have the straw-vote represent the popular will. At the close of the article Chase asks 14 pairs of questions of which he would only require one of each pair to be answered, such as “Do you want a war with Japan?” or “Do you want to starve Japanese babies by an economic boycott?”, along with “Don’t you think it’s silly that, after fifteen years of trial, we still don’t recognize Russia?” paired with “Do you want to recognize Russia and see Communist propaganda broadcast throughout the United States?” After including his entire ballot of questions, Chase closes the article noting, “The great merit to this form of straw-vote would be that the answer to every question is ‘No;–a type of balloting which appeals to everyone–and that the results would be clear-cut and decisive.”

Next up we have an article about and titled “Hindenburg of Germany” by Richard Von Kuhlmann which includes an interesting group of photos of Hindenburg surrounding the text, each dated and titled ranging from “The Cadet, 1860,” through to “The Field Marshall, 1917,” and ultimately “The President, 1932.” There’s an editor’s note informing readers that von Kuhlmann was Germany’s Foreign Minister at the close of World War I, and his article appears to be an insider’s history of von Hindenburg from the war years up through his Presidency. Paul von Hindenburg is also found on the cover of this issue, illustrated by Jean Oberle, illustrator, painter, portraitist, who would go on to be a journalistic for the French Resistance in World War II.

Steichen’s portrait of Lupe Velez stares across the page at “The Theatre” by George Jean Nathan, usually associated with H.L. Mencken as co-editor of both The Smart Set and The American Mercury, critic Nathan was known for his being very rough with his criticism for his time. In this article Nathan compares criticism to reviews noting the difference as the critic doing his work in retrospect while the reviewer must crank out regular reviews as quickly as he can to meet deadlines for his newspaper. Doing so, the reviewer trashes about two-thirds of all plays while praising a third, considered by Nathan to be an honest and accurate amount, but with the problem being that the casual theatregoer seems then to read nothing but negative reviews and comes to the conclusion that the theatre as a whole is suffering while that not be the case at all. To prove his point, Nathan closes his article by recommending two of the better current productions, Eugene O’Neill’s Mourning Becomes Electra and Denis Johnston’s The Moon in the Yellow River, while at the same time taking them down a notch in doing so:

“…the former, while attesting anew to its author’s preeminence among American dramatists and while still another example of his uncommon dramaturgic virtuosity, impresses me as being comparatively a less important work in his canon than his directly antecedent play, Strange Interlude. The Johnston play, while here and there regrettably diffuse, is nevertheless, it seems to me, the worthiest and certainly the most beautifully sensitive play that has come out of Ireland in a number of years.”

Next is a full page of photos showing cast members from four stage versions and the classic film version of Vicki Baum’s “Grand Hotel,” including an image of Garbo alongside her Broadway equivalent Eugenie Leontovich, and of Joan Crawford with Wally Beery alongside their Paris counterparts, Suzet Mais and M. Berley.

“Speakeasy of Love” appears to be a short story by Frank Lynn Parke. Only a little over half a page long, it is an interesting period piece with text such as “They were drinking from small glasses containing a liquid served by the proprietor as his interpretation of gin”; and “Having been, in her youth, an eager student of history, she had observed to her own satisfaction that while drunkards have preformed the greatest feats they have not performed them while they were drunk.”

“This was their year of grace” is a full page of a dozen small personality photos, each with a brief paragraph of text next to them. Such as: “Clark Gable tried to break into the movies a few years ago and was gently but firmly repulsed. Last year he appeared with Norma Shearer in A Free Soul, in the role of a racketeer, and over night became a sensation. Now the feminine hearts of the nation beat only for him”; and “William ‘Alfalfa Bill’ Murray, governor of Oklahoma, blossomed in the limelight when he announced his candidacy for the Democratic presidential nomination. Since then, his campaign tactics–often crude, always colorful–have kept him consistently in the public eye.” The other ten making up this dozen: Yusuke Tsurmuri, Samuel Seabury, Pepper Martin, Ellsworth Vines, George Davis, The Grand Duke Alexander, Goeta Ljungberg, Hal LeRoy, Jackie Cooper, and Ely Colbertson.

The campaign season doesn’t appear to have opened to well for F.D.R as the page “Debit and credit items in the balance sheet of the Democratic Party” features Smith vs. Roosevelt and summarizes itself as: “Governor Roosevelt opened his Presidential campaign with his ‘radio speech’. That address was promptly answered by former Governor Smith, in his Jefferson Day speech. Five days later, at St. Paul, Governor Roosevelt delivered a second speech in which–as a result of Mr. Smith’s castigation–he reversed himself. The quotations from these three speeches will illustrate Mr. Roosevelt’s volte-face.” A little historic flip-flopping for us. Sure is strange to read Governor Roosevelt!

Paul Gallico authors “Everlast, 1932”, a review of the Everlast Boxing Record for 1932. This is followed by the Hoyningen-Huene photo of Ina Claire. The following page contains an item under the “Literary Hors D’Oeuvres” section, and thus I assume fiction, “Friday to Monday” by Sylvia Lyon.

Two of Edward Hopper’s paintings are featured on the facing page, “The Lighthouse at Twin Lights, Maine” at the top, and under that “Camel’s Hump–Cape Cod.” A little text under the Lyon story notes this as the third entry to “A Series of American Artists” and gives a little biographical text about Hopper comparing him to Winslow Homer and George Bellows. The trio are referred to as being purely American painters.

“Wanted: A Dictator” is by the Editors and is a proposal to solve the national difficulty. The article picks on four fields of national policy which the Congress has failed and surmises “There is only one answer to this predicament. Appoint a Dictator! Give to the next President the powers he would enjoy in time of war for the duration of the present emergency! At least one-third of Wilson’s war-time measures were in a strict sense illegal and unconstitutional, They were taken because they were necessary. Similar measures are necessary now.” Whether you loved him, hated him or only think of him as a historical figure, it is interesting to note that while far from being a dictator, Roosevelt would exert as much power over the American Presidency as anyone.

While calling for a dictator sounds completely over the top we must remember the time period and only turn back to the front of the issue to see a large ad proclaiming “Money Travels Further in Italy” in the travel section and recall the earlier article about Paul von Hindenburg, then President of Germany to remember it is early 1932 and Hitler is only on the cusp of coming to power while Mussolini is still viewed positively by many Americans. Vanity Fair concludes:

“In this country, Congress has failed utterly to meet the test. Representative Government has collapsed before the clamor of special interests. The American people can give no mandate before November, and the situation is critical. We must declare and immediate truce on party politics and create legally or illegally, an emergency organization, if the executive power is to rescue the national finance and the national credit from the nerveless hands of a lobby-ridden Congress. The alternative is chaos.”

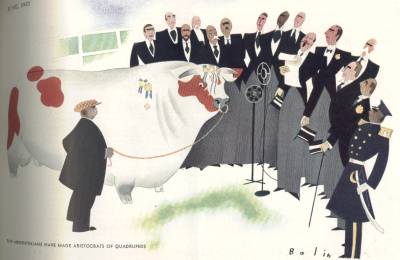

“Argentine Blues” is by Paul Morand with color illustrations by William Bolin, who is one of those figures covered in the opening “Uneasy Chair” where it is noted that he is, “generally known as a ‘fashion’ artist (his work in this field has for years appeared in Vogue) Mr. Bolin’s interest in art covers a wider field. He is a portraitist and a sculptor of ability.” There is also a small photo of Bolin in the editor’s section.

“International week-enders” by Jay Franklin includes several photos of world leaders at the London Conference. The opening line of the article was actually pretty funny: “Ever since two million young American voters took free passage to Europe to make America safer for the Prohibitionists, Washington has been a world capitol.” Franklin goes on to argue in favor of the American delegations presence at the London Conference and debunks “the idea that an American diplomat cannot sit down at the same table with a foreign statesman and arise thence until he has parted with the Monroe Doctrine, American isolation, the national savings account and the family portraits.”

“Bootlegging for Junior” is about bootlegging and the current state of the liquor business, but is more interestingly authored by Dalton Trumbo, then just twenty-six years old. Fifteen years later Trumbo would find himself one of the Hollywood Ten, perhaps the most accomplished and famed of those blacklisted in Hollywood for refusing to testify before HUAC and certainly the one most able to pull his career back together in the aftermath of his blacklisting. Originally working under various pseudonyms, Trumbo finally worked under his own name again in 1960 as screenwriter for Exodus and Spartacus.

“A Man Must Write: An Autobiography of a Heavyweight Novelist” is parody by John “Gene” Riddell, actually the pseudonym of Corey Ford, who has already been noted as writing the text for Covarrubias’ Impossible Interviews. This was a funny article, no kidding. The author’s note tells us that this piece was “encouraged by the popularity achieved by several recent autobiographies of our pugilistic champions–such as Gene Tunney’s A Man Must Fight in Collier’s, and Eddie Eagan’s Fighting for Fun in the Saturday Evening Post. The author, obviously disgusted by fighters treading into his territory, proceeds to discuss his own writing career as though he were a fighter and recounts his rise to become “heavyweight novelist of the world.” Riddell/Ford even manages to rip other writers along the way: “This was of course my first public appearance in the sub-novelist class. I remember that both Dell and Kreymborg were appearing on the same card, as well as a tough newcomer named Harry Kemp, who, I believe is still writing today in the ham-and-egg class.” There are some puns that are groaners, such as “Billy was confident I was a great writer. He used to say even in those early days: ‘Gene, you are the greatest writer I ever Shaw.'” Riddell/Ford takes us through his career up until the famous contest he was to have in Chicago with Dreiser to become heavyweight writer of the world. Of course, if you know your boxing history, you have an idea how this bout would end: “The final count showed I had beaten Jack Dreiser by well over 100,000 words. This became known to fame as the ‘long count’, owing to the fact that it took the referee and two judges well over six months to reach this total.” All in all, puns aside, it’s an excellent piece of writing.

“We nominate for oblivion” has four photos of figures Vanity Fair just wants to see go away. The most notable of this group by far is Adolf Hitler, labeled demagogue under a photo of him raving with both fists clenched. The text explains the nomination: “Adolf Hitler, because his Jew-baiting campaign is medieval in its intensity; because in his efforts to gain votes he played on the strings of feminine hysteria; because, although he advocates strong-arm methods of Change, he has proved to be a sheep in wolf’s clothing; because his gains at the April polls further endanger Germany’s rapport with France.” The other three nominees, far less important, were Floyd Gibbons, Samuel Roth, and William I. Sirovich.

Could you imagine being one of these men a few years later recalling how Vanity Fair had pretty much compared you to Hitler? I don’t know too much about any of this then notorious (to Vanity Fair at least) trio myself, but I certainly don’t find myself thinking kindly of them, which is so wrong, total guilt by association and this is pretty loose association!

“Laying out the garden” is by Corey Ford, under his own name, and illustrated by Dr. Seuss, who Ford refers to in the article when discussing the main problem of laying out a garden–location: “In our effort to settle every question pertaining to the Home Garden once and for all, therefore, Dr. Seuss and I have made a careful study of this neglected phase of the matter.” I will say this, after reading Ford’s piece as “Gene” Riddell above, I don’t think I’m going to take serious gardening tips from him and Dr. Seuss!

On the more serious side, Walter Lippmann writes “Vicious spiral” about how American citizens must eventually end the Depression.

This is followed by “Gebruder Gershwin” by Isaac Goldberg about George Gershwin with illustrations by Constantin Alajalov, best known for his cover illustrations for The New Yorker and Saturday Evening Post, taken from and credited to soon to be published George Gershwin’s Song Book.

“Is Washington done with mirrors” is by “well-known puzzle-maker” Gregory Hartswick and is a series of puzzles combined with political cartoons such as an optical illusion taking the place of Hoover’s brain.

Next up is Clare Booth Brokaw’s piece on Edward Steichen. Again, see the Steichen page on the site if you’re interested in more detail of this article.

“The one over one vs. Culbertson” is about Contract Bridge and by a member of the famed “Four Horsemen,” David Burnstine, who Vanity Fair credits as being “among those chiefly responsible for the perfection of contract bidding and play which the members of that team have demonstrated in winning seven out of a possible eleven national championships in 1931.”

And the last piece to open before the advertisements at the back of the issue begin to filter in is “Query on!” which is a list of 59 trivia questions proposed by Vanity Fair because “the majority of question games confine themselves too rigidly to technical date and remote historical facts, such as how many eggs a sunfish lays in her off years.” Vanity Fair feels it must step in with a more interesting series of questions because “a display of this sort of knowledge doesn’t go very far in adding to your social charm. On the contrary–if nobody stops you–you soon become a handicap at every party.” Among the questions asked are #30 “What is the length of residence required before filing divorce proceedings in (a) Nevada (b) South Carolina (c) Alabama (d) New York and (e) District of Columbia?; and #39 “Who was the male sensation of Hollywood in 1931?” Now the answer to #30 is/was (a)Six weeks (b) no divorce (c)one year (d) Parties must have married in state, or reside in stat when the offense–i.e. adultery–is committed (e) three years. The answer to #39 is actually given elsewhere within this Random Issue, and so I’ll leave it to you to solve!

All right, it’s been a long Random Issue, the answer to #39 is Clark Gable.