The April 1873 issue of The Globe, issued out of Buffalo itself, is Volume 1, Number 1 of a publication which would survive in 1877. The following text of “Mark Twain as a Buffalo Editor” is complete as it originally appeared in that first issue:

Mark Twain as a Buffalo Editor

The Globe, April 1873

The social characteristics of a person of any public prominence have a certain, unspeakable interest. Especially in the case of a noted or popular member of the literati. That which is written in an essay, lecture or magazine article or printed in a book has, of course, its mission to fulfill–an idea to illustrate or sustain, a sentiment to encourage or a theory to advance, or, perhaps, merely the amusement of the mind, but whatever that mission may be its fulfillment entails most impertinent consequences upon the author. Common curiosity is ever rapacious for some knowledge of the inner life of the author whose pen has cheered, interested, amused or offended. Then it is urged that the popular author is the property as well as the pride of his community and no domestic privacy can be tolerated in a man upon whom the great public has set its seal of approval and claimed for its own.

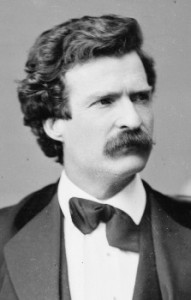

Mark Twain from his writing and his lectures has naturally placed himself most prominently in public view. His brief residence in Buffalo allowed the curious of this vicinity just the least morsel of satisfaction. A quiet, reserved and irritable man, he gave his fellow citizens little opportunity to annoy him with their attentions or questions. Although courteous upon all occasions he was wont to turn a cold shoulder to the staring Paul Prys. The writer has often seen some luckless offending individual scourged beneath the stinging lash of his sarcasm. Mr. Clemens is a bitterly sarcastic man–humorists, as a rule are so–and his uncurbed independence of expression often leads him into unpleasant encounters. His editorial career, when he was one of the proprietors of the Buffalo Express illustrated this quality to a very noticeable extent. The manner in which he wielded the journalistic sceptre was more that of an impatient autocrat than an humble American citizen. His convictions were launched upon the reading public without modification or concessions. Bold and sweeping were the utterances and irreverent the criticisms that he contributed to the columns of the paper. Many there were, too, for when in his working mood Mark Twain’s rapid pen knew little idleness and less constraint. The humorist writes with great ease and accuracy and sends a clean first manuscript to the compositor’s case. Although personally a great stickler for plain Saxon in writing and speaking, it will be noticed that many of his most effective “points” in his humorous sketches are made by his extravagant and reckless mixing up of Queen’s English.

Mr. Clemens, as an Editor of the Express, ever maintained the most rigid views of the power and importance of the Press and was scrupulous of its purity and dignity. He seldom put a word into an article without first knowing and meaning just what that word expressed. And the readers wee also certain of getting his honest convictions most plainly worded. In his spicy salutatory which appeared in the Express on the morning of the 21st of August, 1869, was the following, which when divested of its careless jesting, indicates as clearly as possible Mark Twain’s journalistic platform. We quote:

“I only wish to assure parties having a friendly interest in the prosperity of the journal that I am not going to hurt the paper deliberately and interntionally at any time. I am not going to introduce any startling reforms or in any way attempt to make trouble. I am simply going to do my plain, unpretending duty,–when I cannot get out of it. I shall work diligently and honestly and faithfully at all times and upon all occasions, when privation and want shall compel me to do it. In writing I shall always confine myself strictly to the truth, except when it is attended with inconvenience. I shall witheringly rebuke all forms of crime and misconduct except when committed by the party inhabiting my own vest. I shall not make use of slang or vulgarity upon any occasion or circumstance, and shall never use profanity except in discussing house rent and taxes. Indeed, upon second though I will not even use it then for it is unchristian, inelegant and degrading. I shall not often meddle with politics, because we have a political editor who is already excellent and only needs a term in the penitentiary in order to be perfect. I shall not write any poetry unless I conceive a spite against the subscribers.”

The first two months of Mr. Clemens editorial career in Buffalo were indeed busy ones. From eight o’clock in the morning until ten, eleven and sometimes twelve o’clock at night he sat at his desk poring over exchanges, penning witty paragraphs, exchanging frequent remarks with his associate and writing brief editorials. This was in the summer, be it remembered, and the humorist editor was a picture and a study in himself. Coatless, sometimes vestless, he lolled in his chair with one shoeless foot on the table and the other in the wastebasket. His collar, cuffs and tie were strewn on the floor with the papers, and his hat lay just where it happened to fall when brushed off the back of his head. But he was a worker, and doubtless at the present time the subscribers of the Express bear in delightful remembrance the fresh, agreeable editorial paragraphs that bore, so unmistakably, the stamp of Twain’s matchless sarcasm and humor.

The first two months of Mr. Clemens editorial career in Buffalo were indeed busy ones. From eight o’clock in the morning until ten, eleven and sometimes twelve o’clock at night he sat at his desk poring over exchanges, penning witty paragraphs, exchanging frequent remarks with his associate and writing brief editorials. This was in the summer, be it remembered, and the humorist editor was a picture and a study in himself. Coatless, sometimes vestless, he lolled in his chair with one shoeless foot on the table and the other in the wastebasket. His collar, cuffs and tie were strewn on the floor with the papers, and his hat lay just where it happened to fall when brushed off the back of his head. But he was a worker, and doubtless at the present time the subscribers of the Express bear in delightful remembrance the fresh, agreeable editorial paragraphs that bore, so unmistakably, the stamp of Twain’s matchless sarcasm and humor.

No man detested loafers more than Mr. Clemens, and assuredly no man could be more pitiless in his treatment of bores. He was vigorous in his denunciation of that class of people who aimlessly and impudently intrude their constant presence in an editorial room. One incident will, perhaps, bear relating, showing how he once rebuked a party of undesired visitors. Arriving at his office one evening about half past eight o’clock he found it full of men–all strangers to him. They had apparently taken full possession of the room. Some were smoking and some had their feet upon the table and every chair in the room was occupied. With a look of disgust Mr. Clemens hesitated for a moment in the doorway and then in his peculiar drawling way, said:

“Is this the editorial room of the Express?”

“Yes sir!” promptly chorused the assemblage.

“H–m! is it customary for the editors to sit down?” questioned the humorist.

“Yes,” “certainly,” “to be sure,” were the replies returned by the puzzled smokers. “Why do you ask?” said one of them.

“Because,” slowly enunciated Mr. Clemens, “I am one of the editors of the Express, an it occured to me that I ought to have a seat!”

In an instant every chair was vacated and the men, somewhat abashed, attemtped to laugh the matter off by saying “Ah! Mr. Clemens that was neat,” “witty as ever.” etc., etc., but there was something in the joker’s eye that quickly told them he was in no joking frame of mind at that moment. After that, loungers were rather shy of Mark Twain.